1. Introduction

Rainfall is the main driver of water availability and hydrological variability, and it strongly shapes how water resources are distributed across space and time (Trenberth, Shea 2005). Changes in rainfall directly affect runoff generation, flood occurrence, and drought development, making precipitation a central factor in water resource assessment and risk management (Mishra, Singh 2011). In Ethiopia, where agriculture is predominantly rain-fed, seasonal rainfall variability has far-reaching consequences for crop production, livestock, public health, and the wider economy. The country is especially sensitive to climate extremes because even modest shifts in rainfall timing or intensity can affect food security, land degradation, and water availability (Viste, Sorteberg 2013; Fazzini et al. 2015). Ethiopia also plays a critical regional role as a source for several major transboundary river basins in northeastern Africa, increasing the importance of understanding its rainfall dynamics (D’Souza, Jolliffe 2017).

Ethiopia’s rainfall regime is commonly divided into three seasons: Bega (October-January), Belg (February-May), and Kiremit (June-September). These seasons are mainly controlled by the seasonal movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and its interaction with large-scale atmospheric circulation systems (Gissila et al. 2004; Jury 2018; Nicholson 2018; Aniley et al. 2025). Bega is generally dry and dominated by northeasterly winds, although limited rainfall occurs in southern and southeastern parts of the country (Jury, Funk 2013; Jury 2023). Belg is a shorter and more variable rainy season, influenced by tropical convection and moisture transport from the Arabian Sea (Ding, Sikka 2006; Jury 2010; Viste, Sorteberg 2013; Camberlin 2018). This season is particularly important for the Rift Valley, Genale, Shebelle, and Ogaden basins, but recent studies report a declining trend in Belg rainfall over eastern Ethiopia linked to ocean warming and circulation changes (Jury, Funk 2013; Mera 2018; Stojanovic et al. 2022; Jury 2023). Kiremit, driven by the summer monsoon and enhanced by tropical jet systems, is the main rainy season and provides most of the country’s annual rainfall (Segele, Lamb 2005; Korecha, Barnston 2007; Viste, Sorteberg 2013; Jury 2022). Supporting the bulk of national food production, Kiremit is the most critical season for both agriculture and water resources (Fazzini et al. 2015; World Bank 2018; Abebe et al. 2022).

Variability in these rainfall seasons often leads to extreme events such as droughts and floods, with direct impacts on ecosystems, water availability, and agricultural productivity (Wagesho et al. 2013; Nicholson 2017; Zeleke, Damtie 2017; Mera 2018). Understanding how seasonal rainfall is changing across different river basins is therefore essential for climate adaptation, sustainable water management, and policy development in Ethiopia (de Sherbinin et al. 2008; Shortridge 2019; Moges, Bhat 2021; Gashaw et al. 2023; Kobe 2023).

While several studies have examined rainfall trends in Ethiopia, most focus on individual regions, short time periods, or single seasons. Basin-wide comparisons that consistently assess seasonal rainfall variability across all major river basins using long-term datasets remain limited. To address this gap, this study combines gauge observations and satellite-based rainfall data to analyze seasonal and annual rainfall trends and variability across Ethiopian river basins. By identifying basin-specific patterns and contrasts, the study aims to provide information directly relevant to agricultural planning, water resource management, and climate resilience efforts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Description of the study area

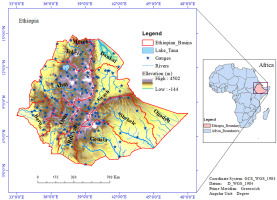

Ethiopia, spanning approximately 1.13 million km2 between 3.30°–15°N and 33°–48°E, is characterized by diverse and complex topography, including highlands, rugged terrain, low plains, and the Great Rift Valley, which divides the country into distinct regions (Fig. 1). Elevations range from 144 m below sea level in the Danakil Depression to 4,620 m asl at Ras Dashen peak (Awulachew et al. 2007). This varied terrain contributes to significant spatial and temporal climate variability, including diverse rainfall regimes (Abbate et al. 2015; Fazzini et al. 2015; Camberlin 2018). The country is divided into several major river basins that differ in size, flow, and elevation, with the Abay (Upper Blue Nile) Basin being the most prominent in terms of flow and tributaries, while the Rift Valley Basin is the smallest, yet known for its numerous lakes (Williams 2016).

Fig. 1.

Study area showing Ethiopia’s river basins, elevation, and the locations of rain gauge stations used in the analysis.

Ethiopia’s economy is heavily reliant on rain-fed agriculture, which employs the majority of the population and contributes significantly to GDP. However, frequent droughts have led to persistent food insecurity, affecting about 10% of households with high levels of malnutrition and dependence on food aid (WBG 2018; Abebe, Cirella 2023). The country also possesses a large livestock population, highlighting the critical importance of water and climate variability for both livelihoods and food security (WBG 2021; Zerssa et al. 2021).

2.2. Rainfall Data Sources

Daily rainfall data from 1981 to 2023 were obtained from 158 spatially representative rain gauge stations operated by the Ethiopian Meteorology Institute (EMI) (Fig. 1). Seasonal rainfall totals were derived from the daily records following the standard definitions of Bega, Belg, and Kiremit seasons. To complement gauge observations and improve spatial coverage, three gridded rainfall products were evaluated: CRU TS version 4.07 (Harris et al. 2020), CHIRPS version 2 (Funk et al. 2015), and TAMSAT, a long-term satellite-based rainfall dataset developed for Africa (Maidment et al. 2020). The performance of these products was assessed against gauge observations using multiple statistical metrics implemented in the Climate Data Tool (CDT).

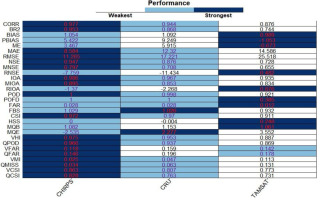

Among the three datasets, CHIRPS showed the best overall agreement with gauge data across most metrics (Table 1).

2.3. Data quality control and homogeneity testing

Quality control procedures were applied to ensure the reliability of the rainfall time series. These included outlier detection, trend testing, and homogeneity assessment following established approaches (Hamed , Rao 1998; Mudelsee 2019; Taylor 2022). Outliers were identified using the interquartile range (IQR) method, where values below Q1 − 1.5 IQR or above Q3 + 1.5 IQR were flagged (Tukey’s method).

Homogeneity of the rainfall series was assessed using the Standard Normal Homogeneity Test (SNHT) (Alexandersson, Moberg 1998), implemented in CDT (Dinku et al. 2022). The SNHT is widely used in climatological studies for its ability to detect artificial shifts caused by changes in instrumentation or station location.

2.4. Seasonal rainfall contribution

The contribution of each season to annual rainfall was calculated as the ratio of the long-term seasonal mean to the long-term annual mean, expressed as a percentage. This allowed comparison of seasonal importance across river basins.

2.5. Temporal and spatial trends

Temporal rainfall trends were analyzed using the modified Mann–Kendall (MK) test, which accounts for serial correlation in hydroclimatic time series (Yue, Wang 2004). The Theil–Sen estimator was used to quantify the magnitude of trends, as it is robust to outliers and non-normal distributions. Spatial trends were analyzed using CDT to ensure consistency across basins.

To minimize the influence of autocorrelation, a pre-whitening procedure was applied before performing the MK test. This approach removes serial dependence while preserving the underlying trend signal, improving the reliability of trend detection.

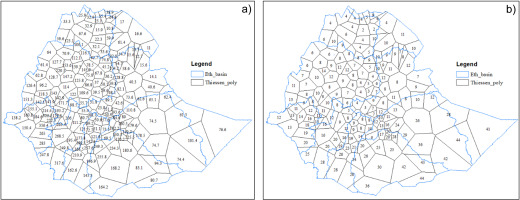

2.6. Areal rainfall estimation

Areal mean rainfall for each basin was estimated using the Thiessen polygon method (Thiessen 1911; Mair, Fares 2011). This method assigns weights to each gauge based on the area it represents, assuming that rainfall within each polygon is best represented by the gauge located at its centroid.

The areal rainfall over the basin (RT) is computed from:

RT = TiRi (1)

Where RT is the observed rainfall at the center of the ith polygon, and the weighting factor Ti is given by:

(2)

Where AT is the total area of the basin or boundary and Ti is the area of each Thiessen polygon.

2.7. Rainfall variability

Rainfall variability was quantified using the coefficient of variation (CV), defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean rainfall, expressed as a percentage (Blöschl, Sivapalan 1997; Pedersen et al. 2010). The CV was computed for individual stations and basin-wide areal means at both seasonal and annual scales. This metric provides a standardized measure for comparing variability across regions and seasons.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Quality control and homogeneity

Quality control checks were carried out using a randomly selected subset of 50 rain gauge stations. Outlier analysis showed that 11 stations contained lower outliers, while only the Amba Maryam station exhibited both lower and upper outliers. These values correspond to known extreme conditions during drought-prone years, such as 1984, and are therefore considered physically plausible rather than erroneous. One upper outlier was detected at the Nedjo station for May 2014 and was traced to an encoding error; this value was removed from the analysis.

Trend and homogeneity testing indicated that most stations did not exhibit statistically significant trends. However, nine stations, including Amba Maryam, Lalibela, Elidar, Jimma, Filtu, Ime, Kebridihar, Axum Airport, and Maytsebri, showed increasing rainfall; Shoa Robit was the only station with a decreasing trend. Five stations (Elidar, Moyale, Filtu, Ime, and Kebridihar) were identified as non-homogeneous and non-stationary. This behavior is likely linked to data gaps and subsequent infilling, which can introduce artificial shifts in the time series.

Overall, the quality control results confirm that the majority of stations provide reliable rainfall records for trend analysis. At the same time, the presence of inhomogeneities in a small number of stations highlights the need for careful screening of long-term rainfall data, particularly when assessing trends at local scales.

3.3.1. Data validation

Data validation was carried out by comparing three satellite-based rainfall products (CHIRPS, CRU, and TAMSAT) to gauge observations using several statistical performance metrics. The aim was to assess how well each product represents observed rainfall and to identify the most suitable dataset for subsequent analysis.

Overall, CHIRPS shows the strongest performance across most evaluation metrics, indicating a high level of accuracy and reliability in capturing rainfall amounts (Table 1). CRU also performs reasonably well but exhibits slightly higher errors and bias compared to CHIRPS. TAMSAT generally shows weaker performance in terms of error-based metrics such as RMSE and MAE. However, it performs better in terms of bias and false detection rates, suggesting fewer false rainfall events and lower systematic error.

Although TAMSAT may therefore be considered a more conservative dataset, CHIRPS provides the best overall balance between accuracy and reliability among the three products. Based on these results, CHIRPS was selected, together with gauge data, for further analysis and graphical presentation in this study.

3.2. Seasons of Ethiopia and their contributions to annual total rainfall

Ethiopia’s three distinct rainfall seasons are Bega (October-January), the dry season with little rainfall; Belg (Feb-May), the second rainy season following the main Kiremit; and Kiremit (June-September), the primary rainy season that supplies the majority of the country’s annual rainfall.

3.2.1. Bega

In southern and southeastern Ethiopia, the Bega season (October-January) represents the second most important rainfall period. Rainfall during this season is mainly associated with the retreat of the summer monsoon and the southward movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Precipitation typically peaks in October and ranges from about 290 to 510 mm in parts of the southeastern Rift Valley, southern Omo, and the southwestern Baro basin (Fig. 2).

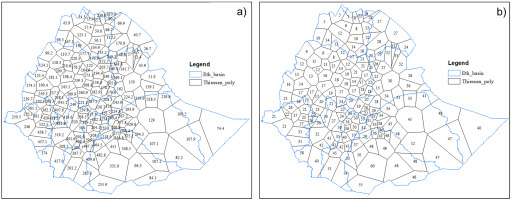

Fig. 2.

(a) Spatial distribution of mean Bega seasonal precipitation and (b) its percentage contribution to annual rainfall, based on gauge observations and corresponding Thiessen polygons.

At the basin scale, the contribution of Bega rainfall to annual totals varies considerably. The Baro and Omo basins receive the highest seasonal mean rainfall during Bega, with averages of 244.7 mm and 258.1 mm, respectively. In contrast, the Tekeze-Mereb and Denakil basins receive much lower rainfall during this season and show relatively high variability. The Genale and Wabishebele-Ogaden basins stand out in terms of proportional contribution, with Bega rainfall accounting for up to 48% of their annual totals (Table 3).

Table 3.

Areal mean seasonal rainfall contribution (%) and coefficient of variation (CV) across Ethiopian river basins .

Other basins, including Abay, Awash, and the Rift Valley, receive comparatively modest Bega rainfall, accompanied by marked spatial and temporal variability. These differences highlight the diverse hydrological behavior of Ethiopian river basins during the Bega season and underline the importance of considering basin-specific rainfall characteristics in water resource planning.

3.2.2. Belg

The Belg season (February-May) is the main rainy period for the Rift Valley, Genale, Shebele, and Ogaden river basins, whereas it functions as a shorter secondary rainy season in other parts of Ethiopia. This season is marked by high temperatures, particularly from March to May, and by strong rainfall variability. In lowland areas, these conditions can increase the risk of wildfires and place additional stress on water and agricultural systems.

Rainfall amounts during Belg vary widely across the country. Southern and southwestern basins such as Abay, Baro, and Omo receive moderate to high rainfall, typically between 250 and 800 mm. In contrast, northern and eastern basins, including Tekeze-Mereb and Denakil, receive much lower amounts, in some locations as little as 17 mm (Fig. 3). Over the past four decades, Belg rainfall has declined by approximately 10-25% in eastern Ethiopia, reinforcing concerns about increasing moisture stress in these regions. Among the basins, Baro stands out as both the wettest and most stable during Belg, whereas Tekeze-Mereb remains one of the driest and most variable.

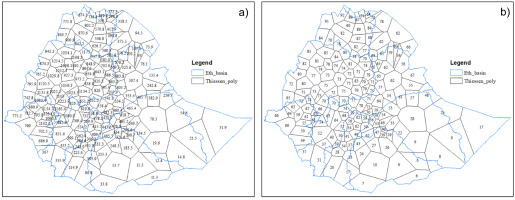

Fig. 3.

(a) Spatial distribution of mean Belg seasonal precipitation and (b) its percentage contribution to annual rainfall, based on gauge observations and corresponding Thiessen polygons.

At the basin level, Belg rainfall contributes a substantial share of the annual total in southeastern Ethiopia. The Genale Basin receives about 100-500 mm during Belg, accounting for 36-60% of its annual rainfall, with a long-term mean of 324 mm (54%), making Belg the wettest season for this basin (Tables 2 and 3). The Wabishebele-Ogaden Basin shows a similar dependence, with Belg rainfall contributing 31-52% of the annual total (mean of 188 mm). The Denakil Basin receives considerably less rainfall, but Belg still accounts for up to one-third of its annual total.

Despite the long-term declining trend, recent years (since 2020) show signs of recovery in Belg rainfall over parts of southeastern and eastern Ethiopia (Fig. 3).

3.2.3. Kiremit

The Kiremit season (June-September) is Ethiopia’s main rainy period, providing the bulk of annual rainfall across most river basins. Rainfall during this season is widespread and relatively consistent, with peaks typically occurring in July and August, coincident with limited temperature variability. Because of its dominant contribution to water availability and crop production, Kiremit is the most economically important rainfall season in the country.

During Kiremit, the Abay, Tekeze–Mereb, and northeastern Denakil basins receive 70-92% of their annual rainfall. Other basins, including Awash, Baro, southern Abay, northern Omo, and the northeastern Rift Valley, receive about 60-70% of their yearly totals during this season. Rainfall amounts show strong spatial contrasts, with western basins receiving the highest totals. Central parts of the Abay Basin and northeastern Baro receive up to 1600 mm, whereas eastern basins such as Genale and Wabishebele-Ogaden receive much lower amounts, typically between 50 and 300 mm (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

(a) Spatial distribution of mean Kiremit seasonal precipitation and (b) its percentage contribution to annual rainfall, based on gauge observations and corresponding Thiessen polygons.

The Abay Basin stands out with the highest seasonal mean rainfall (941.2 mm, accounting for 73% of the annual total) and the lowest variability (CV = 0.07). Baro, Tekeze-Mereb, and Omo also receive substantial Kiremit rainfall, though with higher variability. In contrast, eastern basins such as Genale, Wabishebele-Ogaden, and Denakil receive limited rainfall and show greater spatial variability, particularly in Denakil and Awash, which exhibit the highest CV values during Kiremit (Tables 2 and 3).

3.3. Basin-scale annual areal mean precipitation

Analysis based on CHIRPS rainfall data for 1981-2023 provides a consistent view of the spatial distribution of annual rainfall across Ethiopian river basins. The relatively high spatial resolution of CHIRPS (0.05°, approximately 5 km × 5 km) allows a more detailed representation of rainfall patterns than gauge data alone, particularly in regions with sparse station coverage.

The highest annual rainfall occurs in western and southwestern Ethiopia, notably in the central and southern parts of the Abay Basin, western Baro, and central to northwestern Omo, including areas around Jimma. In these regions, annual rainfall commonly exceeds 1800 mm, with some locations receiving more than 2000 mm. Among all basins, the Abay Basin stands out not only for receiving the largest volume of rainfall but also for its relatively low interannual variability (CV = 0.09), indicating a more stable rainfall regime (Table 3). At the national scale, Ethiopia’s mean annual rainfall is estimated at 813.8 mm, although this average masks strong regional contrasts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basins’ contribution to national annual rainfall total.

In terms of areal contribution, the Abay Basin, covering 199,812 km2, accounts for 28.6% of the country’s total annual rainfall, while the Denakil Basin contributes the smallest share, 2.5% (Table 2). These results underline the dominant role of the Abay Basin in Ethiopia’s water resources. Together with the Tekeze and Baro basins, it supplies more than 80% of the annual flow of the Nile River system, highlighting its regional hydrological importance (Yitayew Melesse 2011).

The mean annual precipitation map for 1981-2023 highlights the strong hydroclimatic contrasts across Ethiopia, largely shaped by complex topography and large-scale atmospheric circulation. The western river basins Abay, Baro, and Omo together receive 52.7% of the country’s total rainfall (Table 2), whereas the eastern basins remain persistently in water-deficit due to their arid and semi-arid conditions. These marked spatial and temporal differences in rainfall underline the uneven distribution of water res ources across the country. A clear understanding of this variability is essential for effective water resource management, agricultural planning, and the design of climate adaptation strategies that are tailored to basin-specific conditions (Wagesho et al. 2013; Ayehu et al. 2021).

3.4. Temporal and spatial precipitation trends

Analysis of both gauge observations and CHIRPS data indicates that rainfall trends across Ethiopia are predominantly positive at seasonal and annual scales. Increasing trends are observed in most basins, particularly during the Kiremit season, which largely controls annual rainfall totals (Table 4; Fig. 5, 6, 7, and 9).

Table 4.

Summary of gauge-based temporal precipitation trends.

Fig. 5.

(a) Bega areal mean precipitation trends based on gauge observations shown using Thiessen polygons and Kendall’s Tau values, (b) corresponding CHIRPS-based precipitation trends (mm yr-1), and (c) the coefficient of variation.

Fig. 6.

(a) Belg areal mean precipitation trends based on gauge observations shown using Thiessen polygons and Kendall’s Tau values, (b) corresponding CHIRPS-based precipitation trends (mm yr-1), and (c) the coefficient of variation.

Fig. 7.

(a) Kiremit areal mean precipitation trends based on gauge observations shown using Thiessen polygons and Kendall’s Tau values, (b) corresponding CHIRPS-based precipitation trends (mm yr-1), and (c) the coefficient of variation.

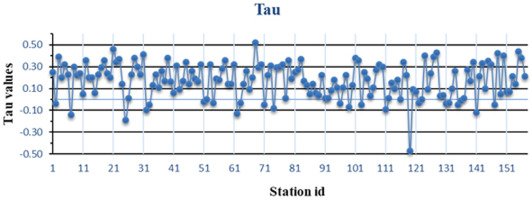

Fig. 8.

Modified Mann–Kendall test Tau values for annual precipitation (1981-2023) based on 158 rain gauge stations.

Fig. 9.

Annual areal mean precipitation trends based on gauge observations shown using Thiessen polygons and Kendall’s Tau values, (b) corresponding CHIRPS-based precipitation trends (mm yr-1), and (c) the coefficient of variation (c).

3.4.1. Bega

Rainfall during the Bega season (October-January) shows pronounced year-to-year variability across Ethiopian river basins. Periods of reduced rainfall commonly coincide with strong El Niño events, while wetter conditions are generally observed during La Niña years, highlighting the influence of large-scale climate drivers on Bega rainfall (Fig. 5).

Despite this interannual variability, long-term trends from 1981 to 2023 indicate a generally stable to slightly increasing pattern. Analysis of rainfall records from 158 stations shows that about 88% of the time series exhibit positive trends during Bega, although most of these trends are not statistically significant (Table 4). Areas with localized decreases are limited and scattered, and the magnitude of decline is small. In contrast, five stations show statistically significant increasing trends, and nearly half of the stations in southern and southeastern Ethiopia record significant increases in Bega rainfall.

Overall, the results do not indicate any widespread or systematic decline in Bega precipitation at the basin scale. Instead, the observed patterns suggest that Bega rainfall remains relatively stable, with modest increases in some regions, particularly in the southern and southeastern basins.

3.5.2. Belg

Between 1981 and 2023, Belg rainfall (February-May) shows strong spatial and temporal variability across Ethiopian river basins. Analysis of the 158 gauge time series indicates a mixed pattern, with 57% of stations showing increasing trends and 43% showing declines. This contrast is most evident between the eastern and southern parts of the country. CHIRPS data confirm a widespread decline in Belg rainfall over eastern basins, including Awash, Genale, the Rift Valley, and Wabishebele–Ogaden, along with localized decreases in parts of the Abay and Baro basins. At the same time, many areas continue to show stable or increasing trends, particularly in southern and southeastern Ethiopia (Fig. 6).

The strongest trend signals highlight the uneven nature of Belg rainfall change. Nekemte shows a highly significant positive trend (p ≤ 0.01), while Adele and Bale Robe exhibit highly significant negative trends at the same confidence level (Fig. 6a). At a less strict significance threshold (p ≤ 0.1), 15 stations (9.5%) display strong negative trends, whereas 16 stations (10.1%) show strong positive trends. Overall, about one-quarter of the stations record statistically significant increases in Belg rainfall, mainly concentrated in southern and southeastern basins (Table 4).

Because Belg rainfall is critical for land preparation, early crop establishment, and the transition to the main Kiremit season, these trends have direct implications for agricultural planning (Diro et al. 2011). Declining Belg rainfall in eastern basins increases the risk of early-season drought and water stress, while increasing trends in southern Ethiopia may enhance cropping opportunities and seasonal water availability. These contrasting patterns reinforce the need for region-specific water management and adaptive strategies that reflect local rainfall behavior (Gudina et al. 2025). 3.5.3. Kiremit

Kiremit (June-September) is Ethiopia’s main rainy season and plays a central role in agriculture, hydropower generation, and overall water availability. Analysis of areal mean Kiremit rainfall trends from 1981 to 2023, based on both gauge observations and CHIRPS data, reveals pronounced spatial variability across Ethiopian river basins.

Most basins show a tendency toward increasing Kiremit rainfall. The Abay Basin, in particular, exhibits a clear upward trend, despite some local declines, reinforcing its importance for rain-fed agriculture and its contribution to the Blue Nile system. The Baro-Akobo Basin also shows a consistent increase in rainfall, which supports both transboundary river flows and agricultural water supply. Similarly, the Omo-Gibe Basin displays increasing rainfall trends, with positive implications for hydropower generation and farming activities. The Tekeze Basin shows moderately positive trends, while the Awash and Genale-Dawa basins exhibit mixed behavior, with increasing rainfall in upstream and midstream areas but declines in downstream sections (Fig. 7).

In contrast, Kiremit rainfall shows declining tendencies in the Rift Valley and Wabishebele basins. Given existing water scarcity and the dependence of local livelihoods on seasonal rainfall, these declines are a cause for concern. Reduced Kiremit rainfall in these basins may increase drought risk, limit irrigation potential, and place additional pressure on water supply systems.

Statistical testing confirms the dominance of increasing trends during the Kiremit season. The Mann–Kendall test indicates that 130 time series (82%) show increasing trends, while 26 (16%) show decreases. Strong positive trends at the highest confidence level (p ≤ 0.01) are observed at 29 stations, mainly in the Abay, Awash, and Wabishebele basins. Strong negative trends at the same level are rare and are observed only at the Shewa Robit station in the Abay Basin. At a lower significance threshold (p ≤ 0.1), strong positive trends occur at 63 stations, particularly in the Abay, Tekeze, and Denakil basins, while strong negative trends are limited to seven stations (Table 4). Overall, the results indicate that increasing Kiremit rainfall is the dominant signal across Ethiopia, although localized declines point to emerging water stress in some basins.

3.5.4. Annual precipitation trend

Trends in areal mean annual precipitation over Ethiopia from 1981 to 2023 were assessed using both gauge observations and CHIRPS data, applying the modified Mann–Kendall test. Trend direction and significance were evaluated using the Tau statistic and associated p-values. Results from both datasets indicate an overall increase in annual rainfall, although the level of significance differs between them. The gauge data show a highly significant upward trend (p < 0.001), while CHIRPS indicates a moderately significant increase (p < 0.05), suggesting a persistent long-term rise in annual precipitation across the country (Fig. 9).

Spatial patterns derived from gauge data are illustrated using Thiessen polygons, where each polygon represents the area closest to a rainfall station (Fig. 9a). Tau values range from −0.47 to 0.50, with positive values indicating increasing rainfall and negative values indicating declines. Most stations show positive trends, and 21 gauges exhibit significant increases (Tau ≈ 0.36-0.52). The strongest increases are observed at Amde Work in the northeastern Abay Basin, consistently identified by both gauge and satellite datasets. In contrast, only one station, Shewa Robit, shows a strong and significant decreasing trend (Tau = −0.47) (Table 4; Fig. 8).

The gauge-based analysis reveals marked spatial variability. Strong positive trends dominate northeastern, central, and southeastern Ethiopia, while parts of the western region show weaker or mixed signals. This spatial heterogeneity reflects regional differences in climate forcing and has important implications for basin-level water availability and agricultural planning.

CHIRPS-based trend maps (Fig. 9b) provide a broader spatial perspective and generally support the gauge-based findings. Western and southwestern Ethiopia show the strongest increases, reaching up to 12 mm per year. Central Ethiopia exhibits mixed trends, while eastern regions mostly show weak increases or near-stable conditions. Although local variations remain, both datasets consistently indicate a general increase in annual precipitation across Ethiopia, with the most pronounced changes occurring in the western basins.

3.6. Basin-scale areal mean precipitation trends

Analysis of areal mean precipitation trends at the basin scale reveals clear contrasts in how rainfall is changing across Ethiopia. The Abay Basin shows a statistically significant increase in both annual and Bega rainfall, along with a notable upward trend during the Kiremit season. In contrast, the Awash Basin does not exhibit any statistically significant trends across seasons or in the annual series.

The Baro Basin stands out for showing consistent and significant increases across all time scales, including annual, Kiremit, Belg, and Bega rainfall. The Denakil Basin shows a significant increase only during the Kiremit season, while the Genale Basin exhibits a significant increasing trend during Bega. The Omo Basin records significant increases in annual and Bega rainfall, and the Rift Valley Basin shows similar significant increases in both annual and Bega precipitation.

By comparison, the Wabishebele and Tekeze basins do not show statistically significant trends in any season or in the annual totals (Table 5). These basin-specific differences highlight the uneven nature of rainfall change across Ethiopia and reinforce the importance of considering individual basin characteristics when assessing climate impacts on water resources and planning adaptation strategies.

Table 5.

Temporal trends in areal mean precipitation across Ethiopian river basins.

Summary and conclusion

This study examined the spatial and temporal variability of seasonal and annual rainfall across Ethiopia’s major river basins using gauge observations and CHIRPS data for 1981-2023. The results confirm that Ethiopia’s rainfall regime is highly variable, shaped by complex interactions among large-scale circulation systems, including the seasonal migration of the ITCZ, the Somali Jet, and tropical easterly flows.

The main findings can be summarized as follows:

Ethiopia’s mean annual rainfall is 813.8 mm, with strong regional contrasts. The western basins – Abay, Baro, and Omo – receive 52.7% of the country’s total precipitation, while the Abay Basin alone accounts for 28.6%, underscoring its dominant role in national and downstream water availability.

Kiremit is the primary rainy season, contributing about 58.2% of annual rainfall nationwide. Belg and Bega provide critical rainfall in specific basins, particularly in the Rift Valley, Genale, and Shebele-Ogaden, where livelihoods depend on rainfall outside the main Kiremit season.

Trend analysis shows that rainfall has generally increased across most basins and seasons, with 88% of the time series exhibiting positive trends. The strongest increases occur in the Abay and Baro basins, with annual rainfall rising by up to 8.1 mm per year.

In contrast, Belg rainfall shows declining trends in eastern basins such as Awash, Genale, and Shebele-Ogaden, where rainfall is essential for early crop establishment and pasture availability. The Shebele-Ogaden Basin also exhibits a consistent decline in annual and Kiremit rainfall, indicating increasing vulnerability to water stress.

Variability analysis highlights marked spatial differences. The Abay and Baro basins show relatively stable rainfall regimes (CV ~ 0.09), whereas the Tekeze-Mereb and Denakil basins experience much higher variability (CV > 0.3).

Reliability for agriculture and water resources was further supported by the CV analysis, which showed significant spatial variability: the Abay and Baro basins had the most stable rainfall regimes (CV ~0.09), while the Tekeze-Mereb and Denakil basins had the highest annual rainfall variability (CV > 0.3).

These findings have direct implications for water resource management and climate adaptation in Ethiopia. Increasing rainfall in western basins offers opportunities for improved water storage, irrigation development, and hydropower generation. At the same time, declining and highly variable rainfall in eastern basins highlights the need for targeted adaptation measures, including drought preparedness, improved pasture management, and investment in water-harvesting infrastructure.

Overall, this study provides a basin-scale perspective on Ethiopia’s rainfall dynamics that can support evidence-based planning and climate-resilient water management. Future work should integrate hydrological modeling with higher-resolution climate projections to better assess impacts on streamflow, agriculture, and water security.