1. Introduction

Long-term changes are coupled with extreme weather events, which are difficult to identify and classify, and therefore difficult to simulate and even more difficult to predict (Royer 2024). Climate events are classified as extreme when a meteorological or climatic variable exceeds (or falls below) a threshold close to the upper (or lower) limit of the range of values observed for that variable (ONERC 2018). Climate extremes and their impacts are now recognised as one of the greatest challenges facing the world through its people, environment, and economies (IPCC 2021).

Extreme precipitation has become increasingly frequent as the climate changes. These events have multiple impacts on humans and the environment. Extreme precipitation causes flooding, soil erosion, reduced agricultural productivity, and crop and livestock losses. It can also cause extensive damage to infrastructure, leading to economic losses and sometimes loss of life. Significant efforts have been made worldwide to anticipate the consequences of extreme precipitation. Future climate simulations under various scenarios are developed to analyze future precipitation trends. These scenarios range from SRES (Special Report on Emission Scenarios) scenarios (IPCC 2007) to SSPs (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways) scenarios, including RCPs (Representative Concentration Pathways) scenarios. Numerous studies at global, regional, and local levels have examined trends and changes in precipitation and other meteorological variables using these simulations. Efforts have also been made to develop extreme climate indices. For example, the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCCDI) has recommended several extreme precipitation indices (Zhang et al. 2011). These indices have enabled significant progress in the study of the future climate.

In West Africa, Odoulami and Akinsanola (2018) detected a significant downward trend in the number of dry days and a significant upward trend in the number of wet days in the Sahel. Diatta et al. (2020) indicated a downward trend in dry conditions in the Sahel and Sahara, while an upward trend was observed in the west and south of the Sahel. Atiah et al. (2020) indicated a significant downward trend in wet indices around Lake Volta and in central Ghana, whereas upward trends were detected over northern Ghana. In Benin, Attogouinon et al. (2017) reported no strong trends in extreme precipitation indices in the upper Ouémé basin. N’tcha M’po et al. (2017) showed that the number of days with heavy and very heavy precipitation, the number of consecutive wet days, the number of wet days per year, and total precipitation are declining at most of the precipitation stations in the Ouémé basin. Hounguè et al. (2019) reported an intensification of heavy precipitation, a simple daily intensity index (SDII), and a decrease in consecutive wet days (CWD) on the Ouémé delta in Benin. Obada et al. (2021) studied the spatio-temporal variability of extreme precipitation across Benin. The intensification of these phenomena, coupled with constant population growth and urbanization, suggests that flooding in Benin’s watersheds will worsen. However, these studies were based on observed data and simulations based on RCPs scenarios, and no study has been conducted on the future evolution of precipitation in the Okpara basin, despite its proven importance in supplying water to the city of Parakou. Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are climate change scenarios that describe alternative global socioeconomic futures up to 2100, detailing different trajectories for population, economic development, technology, and environmental policy. Combined with greenhouse gas emissions, they provide context for climate models and inform policy responses. As with the RCP scenarios, it is important to know: What is the trend in extreme precipitation in the Okpara basin under these scenarios? What are the changes in extreme precipitation indices compared to the recent past, and what are the implications for the environment and populations? The purpose of this study is to examine trends and changes in extreme precipitation indices in the Okpara basin in Nanon under SSP scenarios. This study is important because prior knowledge of the impact of climate change on extreme precipitation will raise awareness, lead to more rigorous climate change policies, and improve preparedness for the consequences of extreme precipitation. Knowledge of the impacts of climate change on extreme precipitation in the future would therefore be a major asset in the process of sustainable development and environmental protection in a region highly vulnerable to climate change.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area and data

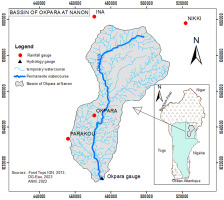

The Okpara watershed at the Nanon outlet is characterized by a crystalline peneplain interspersed with hard-rock hills. It spans 2,070 km2 and encompasses all or parts of five communes in the Borgou Department: Tchaourou, N’Dali, Pèrèrè, Nikki, and Parakou (PNE-Bénin 2008). Geographically, it is situated between 9°4’59’’ and 9°52’40.61’’ N, and 4°6’49.5’’ and 4°37’11.5’’ E (Fig. 1).

Observed daily precipitation (1951-2020) from five in situ stations (Ina, Nikki, Okpara, Parakou, and Tchaourou) was obtained from the Agence Nationale de la Météorologie (Météo-Bénin). The observed data are supplemented with simulations from climate models. In the Inter-model Comparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), a combination of Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) and Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios (Riahi et al. 2017) was developed. Among these scenarios, historical, SSP245, and SSP585 scenarios from the AWI-CM, INM-CM, and EC-Earth3 climate models (Table 1) were used. These models were selected for their high spatial resolution and ability to reproduce extreme rainfall events in West Africa (Agyekum et al. 2022; Lebeza et al. 2024).

2.2. Methods

Prior to using climate model data, bias correction needs to be applied at local scales (Wörner et al. 2019). Bias correction addresses biases in model output that result from how physical processes are captured in the original climate models, their boundary and initial conditions, and the effects of the numerical algorithms used for solving the partial differential equations within the model (Alamou et al. 2022). Bias correction also removes errors due to the large spatial scale of grid cell models that can vary with local climate specificity (Alamou et al. 2022). The ISI-MIP method (Hempel et al. 2013) is used in this study to bias-correct climate model simulations (historical, SSP245, and SSP585).

To assess trends in precipitation and temperature indices, the Mann-Kendall test (Mann 1945; Kendall 1975) was used. The non-parametric Mann-Kendall test is commonly used to detect monotonic trends in series of meteorological, hydrological, and environmental data (Bera 2017; Yu et al. 2017). The main advantages of the Mann-Kendall test are (1) low sensitivity in homogeneous time series (Jaagus 2006) and (2) there is no assumption of normally distributed residuals (Tabari, Talaee 2011).

To find whether the means of the projected periods are statistically different from the mean of the reference period, Student’s t-test was used. Under the null hypothesis of equal sample means and the alternative hypothesis of unequal sample means, the t-statistic is calculated as in Obada et al. (2021).

2.3. Extreme precipitation indices

To characterize extreme precipitation events in the Okpara Basin at Nanon, we investigated eight indices of extreme precipitation recommended by the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices (ETCCDI) (Zhang et al. 2011) (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of extreme climate indices used.

3. Results

3.1. Performance of the bias correction

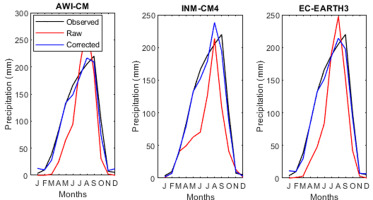

Figures 2 and 3 show the performance of bias correction on precipitation indices. On the one hand, these results show that the ISI-MIP method used to correct the data performed well. The figures show that the differences between the raw data from the climate models and the observed data are reduced after the biases have been corrected. Correcting for bias brings the model simulations closer to the observed data. In this way, climate model projections can be used with maximum confidence to study the future evolution of temperature and precipitation extremes in the basin.

3.2. Recent trends in precipitation indices in the Nanon basin

Figure 3 shows the spatial distribution of the frequency indices: consecutive dry days (CDD), consecutive wet days (CWD), and number of wet days (R1mm). The first line of this figure shows that the CDD varies between 44.3 and 164.7 days, with an average of 109.4 ± 20.7 days over the period 1951 to 2020. It shows an increasing gradient with latitude. This index shows a significant upward trend at the 95% threshold throughout the basin, with higher trends recorded to the east of the basin. On average, this trend is about 4 days per decade in the basin. Furthermore, the CDD index shows, through Hubert’s test at the 1% Scheffé test significance level, a breakpoint in 1961 dividing the study period into two sub-periods (1951-1961 and 1961-2020). These two sub-periods have respective averages of 85.291 and 114.431 days.

The CWD varies between 2.9 and 13.2 days, with an average of 5.8 ± 1.4 days. This index decreases as latitude increases, shows an average upward trend of 0.1 days/decade in the basin, and is only significant in the extreme north. There is no break in the CWD.

The R1mm index varies between 46.2 and 102.3 days, with an average of 75.8 ± 9.4 days. It shows a significant upward trend of 0.6 days/decade on average over the northern basin. Similar to CWD, it shows a latitudinal gradient that decreases as latitude increases. The R1mm shows a breakpoint, which is highlighted by Hubert’s test at the 1% significance level of the Scheffé test. This point was detected in 1956. An average of 91.16 days was recorded for the first period (1951-1956) and an average of 76.865 days for the second period (1957-2020).

Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution of the average intensity indices (RX1day, RX5day, R95p, R99p and PRCPTOT), their trends and significance, as well as their chronological evolution and probable breakpoints over the historical period (1951-2020). Figure 5 shows that the RX1day index varies between 52.7 and 141.5 mm, with an average of 78.1 ± 11.2 mm, while the RX5day index varies between 90.5 and 185.5 mm, with an average of 124 ± 17.6 mm. The R95p index varies between 60.3 and 581.6 mm with an average of 228.1 ± 77.8 mm, while the R99p varies between 0 and 251.6 mm with an average of 70.3 ± 35.9 mm. PRCPTOT varies between 671.6 and 1575.3 mm with an average of 1128.8 ± 155.5 mm. The RX5day, R95p, R99p, and PRCPTOT indices show a non-significant downward trend, except for PRCPTOT, which is significant in the northern basin at the 1% threshold. The RX1day is increasing non-significantly at the 1% threshold. Of all the intensity indices, only PRCPTOT shows a breakpoint detected in 1969.

3.3. Future trends and changes in climate indices in the Nanon basin

Figure 5 shows future trends in the CDD and CWD indices of the AWI-CM, EC-Earth3, and INM-CM4 climate models under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios for the period 2030-2099. Under the SSP245 scenario, the AWI-CM model indicates significant increasing trends that vary from 1.5 to 5 days per decade. The EC-Earth3 model indicates decreasing trends of –4.1 to –1.5 days per decade. These trends are significant in the center of the basin. Under the SSP585 scenario, the INM-CM4 model indicates non-significant mixed (downward and upward) trends for CDD. Significant downward trends in CDD, varying from –5.4 to –3 days per decade, are indicated in the northern basin for the EC-Earth3 model, while non-significant upward trends are predicted for the AWI-CM model.

The CWD index shows non-significant upward trends under both scenarios for the AWI-CM. Using the EC-Earth3 model, non-significant downward trends are indicated for the SSP245 scenario, whereas significant upward trends are predicted for the SSP585 scenario across the entire basin. For the INM-CM4 model, regardless of the scenario, the CWD index shows downward trends across the entire basin; the trends are significant for the SSP585 scenario. Overall, the predicted trends for all models and scenarios are very small (less than 1 day per decade).

Figure 6 presents the changes in the CDD and CWD indices under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios (2030-2099) compared to the observation period (1951-2020). The CDD could increase by 0 to 5 days in the southern part of the basin and decrease by 0 to 7 days in the northern part of the basin under both SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios for the AWI-CM model compared to the observation period. The EC-Earth3 model predicts increases of about 7 to 15 days for the CDD under the SSP245 scenario and 6 to 12 days under the SSP585 scenario compared to the observation period. These increases are statistically significant in the central and southern basin. The INM-CM4 model indicates a significant decrease in CDD over the entire basin, varying from 13 to 33 days for SSP245 and from 19 to 40 days for SSP585. The indications are a possible decrease in the dry period in the basin and an increase in the rainy season under these scenarios. The CWD could increase significantly over the entire basin compared to the observation period, regardless of the scenario and the climate model considered. These increases are of the order of 3 to 7 days for the AWI-CM and EC-Earth3 models but relatively low for the INM-CM4 model (1 to 3 days).

Fig. 6.

Changes in CDD and CWD under SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios (2031-2099) compared to historical observations (1951-2020) at Nanon.

Figure 7 shows the future trends of the PRCPTOT and RX1day indices under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios (2030-2099). The three climate models indicate non-significant increasing trends in the basin, except for the INM-CM4 model, which predicts decreasing trends. However, significant upward trends were found over the entire basin with the SSP585 scenario for all models. For the PRCPTOT index, the trends vary from 7.1 to 9.1 mm/year, 9.4 to 13.8 mm/year, and 12.1 to 13.4 mm/year, respectively, for the AWI-CM, EC-Earth3 and INM-CM4 models. For the RX1day index, the trends vary between 6 and 11 mm/decade for the 3 climate models. The RX5day index shows significant upward trends across the basin under the SSP585 scenario for the 3 climate models considered, varying from 12 to 18 mm/decade.

The R1mm index shows downward trends under both AWI-CM model scenarios; significant under the SSP245 scenario, and varying between 1 and 2 days/decade, while the EC-Earth3 and INM-CM4 models indicate significant upward trends under the SSP585 scenario across the basin and vary between 1.1 and 3.5 days/decade for EC-Earth3 and 3.6 and 4.3 days/decade for INM-CM4. These significant increases in the number of wet days are consistent with the increase in PRCPTOT in the basin.

Figure 8 shows the changes in the PRCPTOT and RX1day indices under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios compared to observations. The PRCPTOT and RX1day indices could increase significantly across the basin regardless of the scenario and climate model considered, except for the SSP245 scenario of the AWI-CM climate model, which indicates significant decreases in the south of the basin and non-significant increases in the north. Under the SSP245 scenario, the PRCPTOT index could increase compared to the observation period by 230 to 440 mm/year, 270 to 420 mm/year and 200 to 280 mm/year, respectively for the AWI-CM, EC-Earth3, and INM-CM4 models under the SSP245 scenario compared to increases of 550 to 700 mm/year, 430 to 550 mm/year and 420 to 500 mm/year under SSP585. This indicates that future periods will be wetter than past periods under both scenarios . The SSP585 scenario would be wetter than the SSP245 scenario. The increases are also significant for the RX1day index. They vary from 6 to 16 mm/year under SSP245 and 25 to 45 mm/year under SSP585 for the EC-Earth3 model. For the INM-CM4 model, they vary from 55 and 75 for both scenarios. Regardless of the scenario and climate model, the R1mm and RX5day indices could increase significantly across the basin. The R1mm index could increase by 6 to 14 days/year under both scenarios for the EC-Earth3 and INM-CM4 models compared to 10 to 30 days/year for the AWI-CM model.

4. Discussion

In this study, three global climate models are used for a local-scale study: the Okpara watershed at Nanon outlet. The models have shown sufficient capacity to reproduce the region’s precipitation pattern, making them ideal tools for studying the impact of climate change in the region. However, the models are unable to simulate precipitation amounts correctly, underestimating the dry months and overestimating the wettest months (July-August). These difficulties in simulating the local climate can be explained by the limited spatial resolution of these models, which does not allow them to capture fine-scale phenomena, and by the complexity of the interactions between the components of the climate system. Furthermore, these difficulties may also be due to poor integration of regional boundary conditions (such as ocean currents and topography) and local forcings such as changes in land use. These limitations lead to errors in key variables such as clouds, precipitation, and winds, which are influenced by fine-scale processes.

The ISI-MIP method used to correct model errors has effectively brought the model simulation data closer to the observation data. As a result, the projections using these models in the region would be acceptable.

Over the 2030-2099 period, maximum consecutive wet day (CWD) and maximum consecutive days (CDD) indices show upward and downward trends depending on SSP scenarios and climate models. For the number of wet days (R1mm), maximum daily precipitation (RX1day), maximum precipitation of 5 consecutive (RX5day), heavy precipitation (R95p), very heavy (R99p), and total annual precipitation of wet days (PRCPTOT) indices of all scenarios and models generally display significant upward trends. These results are consistent with those obtained at the global scale with SSPs scenarios (Shi et al. 2021; Anil, Raj 2024, Tavosi et al. 2024; Nazarenko et al. 2025). For Africa, Lagos-Zúñiga et al. (2024) report mixed trends in the Rx5day and CDD indices, with significant spatial heterogeneity in both magnitude and direction using RCPs scenarios. The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events are also expected to increase with rising greenhouse gas emissions in East Africa (Ayugi et al. 2021; Demissie et al. 2025). Similar results are reported by Ebedi-Nding et al. (2024) for Central Africa. In the far future (2071-2100), intensified wet conditions are expected on the Guinea Coast under SSP585, according to Ilori and Adeyewa (2025).

The upward trends observed for most of the extreme precipitation indices led to a significant increase in these indices under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios over the period of 2030-2099 compared to the reference period (1951-2020). This suggests an intensification of wet conditions in the future in the Okpara basin. This intensification could increase the risk of flooding (Aryee et al. 2024). Other consequences of this warming are an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) and population exposed to hazards (Shi et al. 2021; Yang, Zhao 2024). These trends reveal a need for specific management and adaptation strategies focused on flooding. The findings of this work could provide useful information for the development of climate change mitigation and adaptation policies in a region that is highly vulnerable to the consequences of climate change due to a constantly increasing population and a lack of adequate adaptation strategies (Diatta et al. 2020). The various development programs of the municipality of Parakou should account for these aspects to preserve the safety of people and property, and with the aim of efficiently managing possible water-related crises.

5. Conclusion

The analysis of precipitation indices in the Okpara Basin at Nanon over the period 1951-2020 shows non-significant increasing trends for consecutive wet days (CWD), number of wet days (R1mm), and maximum daily precipitation (RX1day). Maximum consecutive dry days (CDD), maximum precipitation of 5 consecutive (RX5day), heavy precipitation (R95p), very heavy precipitation (R99p), and total annual precipitation of wet days (PRCPTOT) indices indicated non-significant downward trends. Projections from AWI-CM, INM-CM4, and EC-Earth3 climate models under the SSP245 and SSP585 scenarios indicate statistically significant upward trends for most of the indices, leading to a statistically significant increase of these indices in the future related to the observation period. An intensification of wet conditions is therefore expected in the basin, and it is important that basin managers, planners, and decision-makers must develop strategies to prevent and properly manage possible water-related crises in the basin.